Drug use by soldiers declining

In December 2007, in the Journal of the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), I highlighted an increased cocaine positive rate in the British Army between 2003 and 2007. I’d relied on answers to parliamentary questions by the late Lord Garden and Patrick Mercer MP.

Was the hike in cocaine rate an artefact, a real public health concern or just a reflection of civilian life? It would be a health concern if cocaine use was a reaction to combat stress.

But the army was getting ever smarter at detection, by using a more sensitive cocaine-test and testing preferentially:

- on Mondays – after weekend home leave (cannabis stays in the urine for around two weeks, but cocaine and ecstasy for a few days only)

- younger soldiers, typically privates – who are more recently recruited and from the age-group in which civilian drug use is highest, or

- selected units or individuals – because of historically high detection rates, or other intelligence.

All of these changes happened between 2003 and 2007, and muddied the analytical waters.

A new analysis, efficiently and promptly published, took a revised cocaine threshold, as well as rank and weekday of test into account. It revealed that the increase in cocaine positive rate had already levelled off in 2005 – before major combat in Afghanistan. Also, whereas privates’ cocaine positive rate on Mondays in 2007 was around 10 per 1,000 tests, it had halved by Wednesdays. This strongly indicated that soldiers’ cocaine use was off-duty at weekends, not dependency.

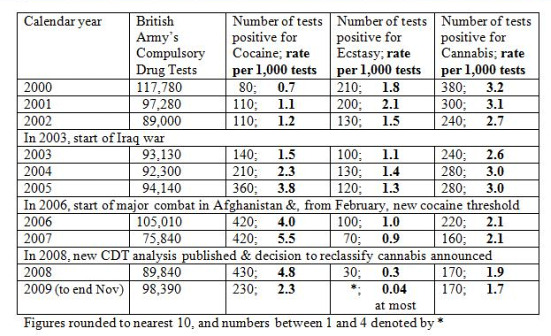

The 2008 analysis also confirmed that the army conducts compulsory drug tests with exemplary efficiency. The major drop in its cocaine positives, which we now see ( in today’s Independent and table below), was not due to any let-up on detection, which the army hell-bent on. The cocaine rate has halved from around 4.7 positive for cocaine per 1,000 tests in 2006-2008 (95 per cent CI: 4.4 to 5.0) to 2.3 per 1,000 tests in 2009. The ecstasy positive rate has also fallen dramatically in 2008 and 2009.

However, the army’s compulsory tests do not include mephedrone, a "legal high", which is cocaine-like. Have soldiers (and civilians) substituted mephedrone for cocaine?

Soldiers and civilians now need to know about the relative harms of cocaine, ecstasy and mephedrone: including lethality. The only way to learn about the lethality of mephedrone is if, as a matter of routine, we start testing for its presence at all drug-related deaths in the UK in a 6-month period. For the sake of public health, this testing should be done.

Anonymous (not verified) wrote,

Thu, 18/03/2010 - 09:33

I was confused by your introduction in the middle of your article of mention of mephredone without any explanation of why that particular legal high, rather than any other ones, now needs to be tested for - where is your statistical or scientific evidence base either for current extent of use or for suggesting its lethality has a worrying high incidence or that it is being used as a substitute - is there evidencce from soldiers to that effect or is it just speculation??

The same sort of concerns as you raise were previously raised about crystal meth when that became much more prevalent in recent years in the US, but those worries in the media and elsewhere subsequently subsided as concerns over a possibe epidemic of its use here didnt, apparently, follow.

Presumably you would want to have a proper scientific criteria and process for assessing and deciding which new legal and illegal highs need to be investigated for switching effects, and how? your articles on this subject imply you are dissatisfied with whatever the existing process is, but you dont explain what it is, how you engaged with it and what the response has been? You dont seem dissatisfied with existing reporting, you praise a report above, so what is the inaccuracy or misleading claim that Straight Statistics is pointing to here, exactly? Is your criticism of MoD, the Research Councils, whoever is responsible for coroners, the Department of Health, or of researchers for not putting forward a research proposal to fill the gap you suggest exists? Or is your complaint a result of having a propsal turned down which decision you disagree with? It's all a bit unclear whom you are criticising and why, and exactly what you propose be done instead...

Based on your arguments, should we not also test for other legal drugs, such as alcohol and tobacco use as well at all drug-related deaths in the UK in a 6-month period, For the sake of public health.

also, why are you proposing a UK wide study before piloting, which is best practice for all new studies?

hope you find this thought provoking and constructive

betclic (not verified) wrote,

Mon, 02/08/2010 - 09:08

Bonjour et merci pour les information bonne continuation betclic